It's time to apply evidence-based guidance to MEP alerts.

- Jeannette Sutton

- 15 hours ago

- 4 min read

Recent research on effective Missing and Endangered Person (MEP) alerts has identified how to name the incident and how to structure a message to be most effective at helping message receivers to understand and respond to messages.

When we consider MEP messages in relation to more general alerts and warnings, they follow the same structure as those warnings that are issued for all hazards. They should always contain the following CONTENTS:

The name of the message source

The name of the hazard/incident

The location of the hazard/incident

The timing of the hazard/incident

Guidance on what people should do to protect themselves or others.

Importantly, the STYLE of the message is similar as well. Messages should be: CLEAR, consistent, and certain. Message CLARITY means eliminating the use of jargon or technical language; making them easy to read; and providing enough information to help reduce uncertainty and delay.

For MEP messages, some of the CONTENTS related to the HAZARD or INCIDENT will differ. Here incident information should focus on a description of the missing person (their age, gender, appearance, specific vulnerabilities) and how they might be traveling (walking, driving, cycling, etc.) Another type of MEP is for persons who may have been abducted or kidnapped. In this case, additional incident information should be provided about the suspect (age, gender, appearance, name) and any details about the vehicle they may be driving. The rest of the message remains largely the same. It is still best to eliminate the use of jargon or technical language and to utilize plain language that is easily understood by message receivers.

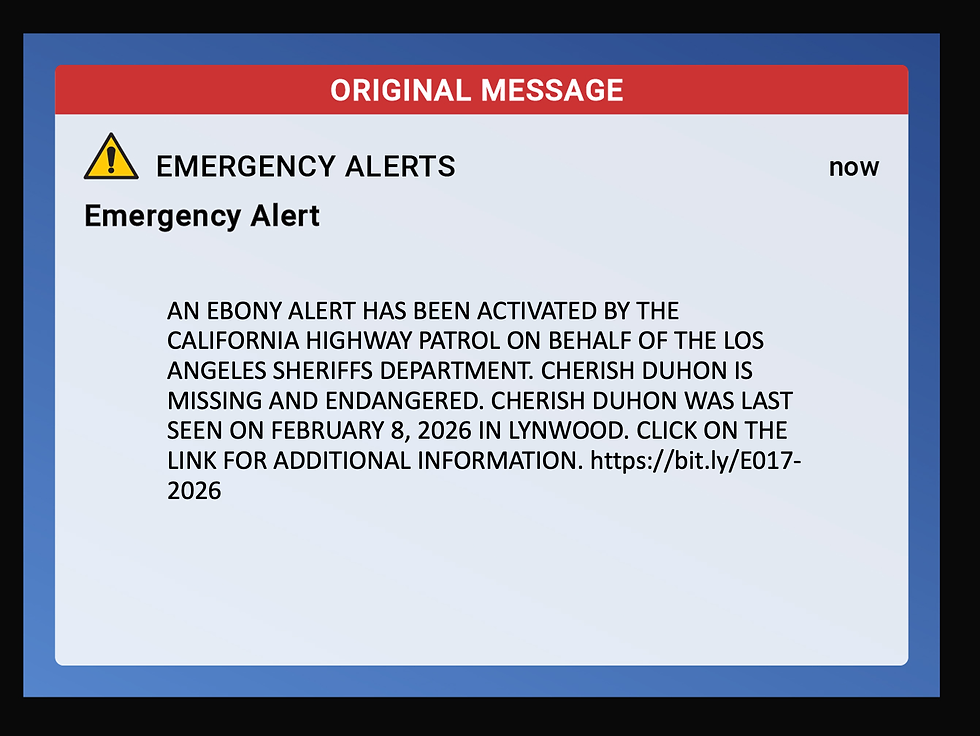

Turning to the message that is the example for today's post, we see a few things that do not conform to the CONTENTS or the STYLE that align with decades of research on alerts and warnings.

We are going to begin with CONTENTS. This message begins with law enforcement jargon. It is an announcement that an "EBONY ALERT HAS BEEN ACTIVATED" and then refers to the source that has issued the message and the source that requested the message be sent. None of this information is relevant to the average message receiver. This is all coded language that indicates there is a legal precedent for message issuance (the incident meets the thresholds for issuing an EBONY alert) and there are authorities that are involved (two agencies are involved in sending the alert through WEA).

If you've read The Warn Room previously, you know that there are more than 40 types of named alerts. Most are STATE specific; some are national-level alerts (AMBER and Ashanti). The name of the alert suggests some feature or aspect of the person who is missing (race/skin color, part of a specific protected group), but they are not always obvious. In our research on public understanding and knowledge of these 40 + different named alerts, with the exception of AMBER alerts, most are unknown or misunderstood. If message senders want receivers to know and understand the conditions of the missing person, utilizing a legal term like "Ebony Alert," will not accomplish this task.

More about CONTENTS. Next we see the name of the person who is "MISSING AND ENDANGERED." No details are provided about the missing person. There is no information about their age, gender, race, or particular vulnerabilities that could help the message reader to understand WHY the person is endangered or WHAT they should look for if they were assist in finding the person. The message concludes with a location, the time last seen, and a link to more information.

In terms of STYLE, the entire message is written in ALL CAPS. Research has demonstrated the importance of using CAPS sparingly for the purpose of easing the task of reading and for helping to draw attention to key words. In our work on alert and warning messages, including studies using eye tracking methods, CAPS serve an additional function of helping to increase recall of the key words that are capitalized. When the entire message is written in ALL CAPS, it is difficult to read, no words are called out for attention, and it is unlikely that specific information will be easily recalled.

The last comment about STYLE is in reference to the use of the link. In this case it is a shortened link in the style of a bitly. In our research on links, we find two issues - first, few people will click on the link. If the link is being used to direct people to information about the MEP and they do not click on it, the message is ineffective at communicating key information. Second, bitly links that are not branded are the least trusted links among public message receivers. Without cues that the link is trustworthy, few people will be willing to click on it to get additional information.

The experimental research that is referenced in this blog is under review for publication in an academic journal and will be available soon. We are also building a MEP lexicon that will assist message writers to develop MEP messages that are based in evidence.

In the meantime, be sure to keep reading The Warn Room blog and download the Warning Lexicon. It's a free resource that can help you to build better messages for all hazards. Plus the evidence applies to ALL hazards and incidents, including alerts for missing persons.

This information may be shared or quoted with attribution.